Hello! This page goes into more details about grouping notation.

If you’re looking for an introduction to the process, look here 🙂

How did grouping notation originate?

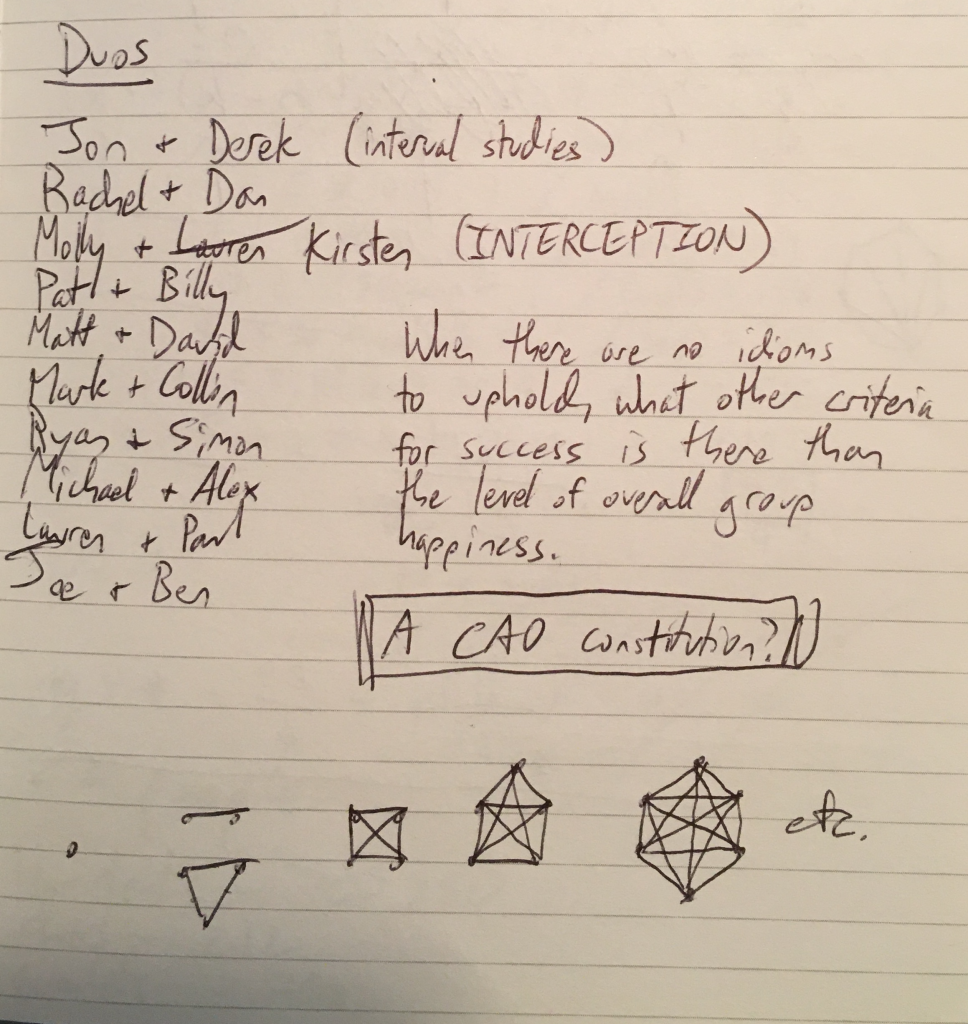

In 2012 I was in the Creative Arts Orchestra at the University of Michigan. Mark Kirschenmann was our director, and he brought us an exercise called

“rolling duos”. Two people in our 20 person ensemble would self-select and play a piece together, followed by another two people, and another, until all of us had played. The duets sometimes overlapped a little bit, and sometimes there was a clean break between them.

It was a very cool exercise, so I decided to take notes:

An excerpt from my notebook, dated February 2nd, 2012, including various thoughts and doodles.

An excerpt from my notebook, dated February 2nd, 2012, including various thoughts and doodles.

I noticed that these duets could be notated with the number “2”, and that the entire exercise could be notated with ten “2”s.

But why stop with 2? One could write a thread of numbers, with membership being determined through self-selection of ensemble members. Composing music using cardinality of people seemed really intriguing, so I decided to keep investigating it.

Anytime a small group of performers is selected (or self-selects) from a larger group of performers, a type of grouping practice is taking place. When that practice becomes notated, then you have a grouping notation.

Is there a theory behind grouping notation?

Yes! It’s quite interesting in fact. Here are the number of relationships (including solos and silence) possible in an ensemble of size n (0-12 people).

| 2n = | Total Groupings Available |

| 20= | 1 |

| 21 = | 2 |

| 22 = | 4 |

| 23 = | 8 |

| 24 = | 16 |

| 25 = | 32 |

| 26 = | 64 |

| 27 = | 128 |

| 28 = | 256 |

| 29 = | 512 |

| 210 = | 1024 |

| 211 = | 2048 |

| 212 = | 4096 |

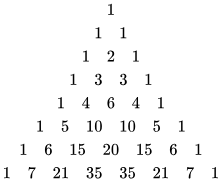

These relationships can be further broken down into a list of silences, solos, duets, trios, quartets and so on, by using the binomial triangle:

Credit: Wikipedia

Credit: Wikipedia

Take the bottom row. An ensemble of seven people has 128 potential relationships, including 7 soloists, 21 duets, 35 trios, 35 quartets, 21 quintets, 7 sextets, and 1 septet. (And as with ensembles of any size, there is always one combination which includes no one.)

Using a process called refraction we can articulate the first, second, third, fourth, and so on, people in any grouping. The symbols I use to indicate firstness, secondness, and so on, are called placeholders:

{α, β, γ, δ, ε … }

In 2015 when I started on this work, I used lower-case Greek letters because they were convenient and looked cool. But as with the groupings themselves, any consistent set of symbols can be used.

Placeholders do not signify particular people. They signify firstness, secondness, thirdness, and so on. So whereas grouping notation measures cardinality, placeholders measure ordinality. Using these symbols, it is possible to fully articulate groupings and transitions. This theoretical notation can also be used in reverse, to compose groupings and transitions via curation (described below.)

What was your first composition to use grouping notation?

In mid-2012 I composed Jacob’s Ladder which was based on the structure of DNA nucleotides. Each hydrogen atom was translated as a solo, each oxygen atom as a duet, each nitrogen atom as a trio, and each carbon atom as a quartet.

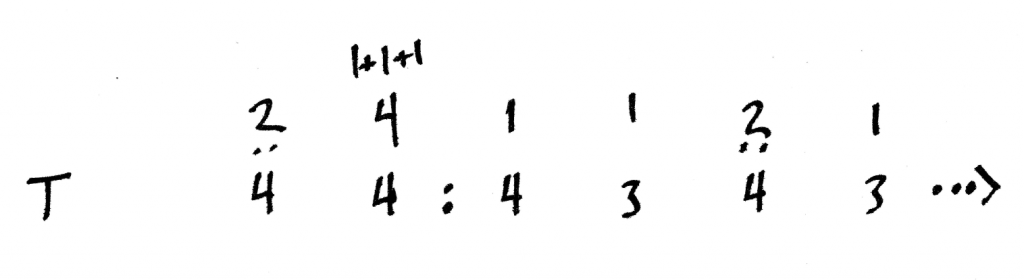

Movement T from Jacob’s Ladder. Calligraphy by Geoff Pfeifer.

Movement T from Jacob’s Ladder. Calligraphy by Geoff Pfeifer.

By interpreting the nucleotide structure in this way, I wrote a score with 150 opportunities to play, composed of 21 solos, 19 quartets, 15 trios and 4 duos, spread across 30 measures. These were distributed among 4 movements,

which are themselves interchangeable in 8 different ways (ATCG, GCTA, etc, the same as the 8 nucleotide combinations.)

An ensemble of 12 implies the availability of 66 duo combinations, 220 trio combinations, and 495 quartet combinations! This ensemble could perform Jacob’s Ladder 26 times and never repeat a quartet configuration. The potential is pretty incredible.

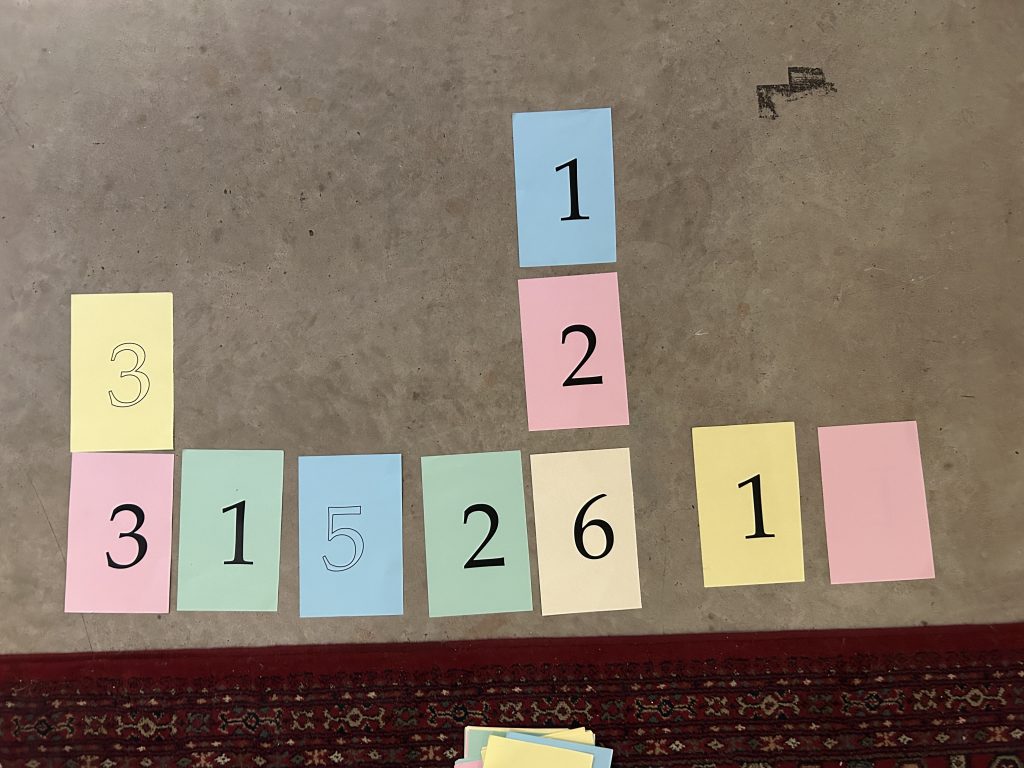

In Bloom, does the colored paper mean anything?

How about the solid vs. outline font formatting?

No, not intrinsically. In the summer of 2025 I printed two additional sets of Bloom cards using coloured paper, and I find they are much more aesthetically pleasing to play with, and to look at.

An example score from September 2025, Guelph ON. The blank card indicates the end of the score.

An example score from September 2025, Guelph ON. The blank card indicates the end of the score.

They also reflect the diversity of personalities and backgrounds in the ensembles that I work with.

No matter how a grouping card initially looks, its compositional intent is only to measure cardinality. However, ensemble members can bring meaning to the colour, font, and formatting through a process called curation.

What is curation?

Curation is a way to make a customize a particular grouping. On their own, the cards do not specify who is a part of a grouping, how these groupings transition to one another, how long each grouping is, and so on. If ensemble members wish, they can customize groupings with specific personnel, instrumentation, musical content/motifs, duration, and so on, in a process called curation.

Examples of curation include:

- This grouping will last for 4 minutes and 33 seconds.

- This grouping will consist of Alice, Bob, and Gary.

- The first person in this grouping will be Alice or Bob.

- The last person in this grouping will be Bob or Gary.

- Only woodwind players (or harpists, or dancers, etc.) can be in this grouping.

- This grouping will be based around a motif or rhythm composed by an ensemble member.

- This grouping will be selected via a process of conduction,

led by the second person to join the previous grouping.

…and so on.

At least in the context of grouping notation, curation is the opposite of indeterminacy. It is a broad concept to give ensembles greater individual control over certain groupings. Curation could also involve changing the appearance of a grouping card, in effect, decorating it.

It is not mandatory: your ensemble can leave the groupings indeterminate if they want to. But just in case, rehearsal time should always be set aside as an open space / floor for people to present their curations.

Can I use grouping notation with my ensemble?

Absolutely! Groupings are just numbers – you can make your own set of grouping cards if you want to, or you can request a set from me.

Go Back