Avant garde on the Escalator

Cross-legged and barefooted, MIKE MANTLER squats on the floor of Lenge's Japanese restaurant in New York and amicably argues the case for the defence regarding his work with the likes of Pharaoh, Cecil Taylor and Don Cherry. By BRIAN CASE.

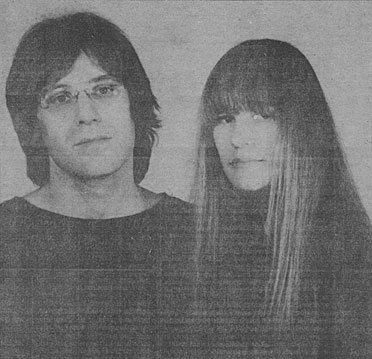

MIKE MANTLER and CARLA BLEY: "I hardly listen to jazz at all" says Mantler

MIKE MANTLER and CARLA BLEY: "I hardly listen to jazz at all" says Mantler

BRIAN CASE: The setting of words to music is a new departure for you. I'm thinking of "How It Is."

MIKE MANTLER: Yeah, that record is the first thing I've done of that sort. We were working on "Escalator" for so long - and I was involved with all those voices as a producer or participator - that I ended up getting very interested. I think I originally suggested we use Jack (Bruce) for "Escalator" - Carla (Bley) knew him, I didn't - but we both liked his voice and the way he sang. I also like him as a composer, and the solo albums he's done are fantastic. Really great.

Did you think my review of "How It Is" fair? I mentioned Palestrina and Brecht with Kurt Weill - justified or not?

No, I don't think so - I mean, yes, I like Kurt Weill a lot. In fact it's the comment that's usually made about Carla that's really inappropriate. Usually they end up saying Carla Bley is influenced by Bertolt Brecht, which is totally ridiculous.

I don't see that.

Well, Brecht writes political words which come out of a very specific social and political scene in Germany. And that has absolutely no relationship to what Carla does.

Both couple music with a philosophy of life.

Yeah but not a political ideology. You can interpret it that way because it's ambiguous, the words are ambiguous - but that's Paul Haines.

Let me be specific. Like Brecht, Carla set the words in conflict with the mood of the music so that the most cynical statements will ride on waltz-time, or tender words tug against circus sounds.

Well, it might happen that way. I don't think it's an influence - I mean not anything conscious.

Were you into new-thing orchestras before "Ascension?"

I'd written for large orchestras long before that happened. I was interested in writing for larger groups because I just didn't find, as a composer, that a small group could express as much. The first "Communication," like Number One, was written around 1961 or 62. It wasn't recorded, so it doesn't exist any more really.

Are your communication pieces exercises in problem-solving?

Well, it's always a matter of form you know. It develops ... each piece develops from the beginning to the end and has its own form. I organise it formally and a lot of things happen - I mean, certain pieces have one formal idea to them, like number. The one with Larry Coryell is a very simple basic idea really ("Communications 9").

Which is the most successful in your view from the point of view of balance between soloist and orchestra?

Eleven probably - Cecil Taylor, and Number Eight - Don Cherry.

The little Pharoah piece is a knockout.

That too. I think they're all successful. Some of them are worse performed than others - let's put it that way - though all the performances are very spirited. Six and 12 are perfectly interpreted because there was total control with only one instrument. Both pieces were written for orchestra originally.

You write your pieces with a specific soloist in mind as a rule, though? Like Ellington or Strayhorn did.

I guess so, yeah. The pieces were written specifically with them in mind. They know who they are, and they know how to play. I'd worked with Cecil Taylor in his group for a long time, so I was like intimately familiar with the music. That's what these pieces were tailored towards. That's why I think there was no problem. They just played the way they play, and it fell right into it. Carla is very instrumental in all that music - I don't write any parts for her, she just gets the whole score.

How much rehearsal for the JCOA album?

Not very much at all. There were about three rehearsals each for each piece, then they were recorded - two records in four three-hour sessions. There wasn't too much splicing ... some, yeah, but they were fairly intact.

Why did you use five bass players? It doesn't come over too well.

Well, I like the idea of it. It's not really successful on the record because they couldn't record it, but you should hear them live! We did some of that music live in concert at the Electric Circus, you know - I was using eight bass players spaced around the orchestra in a circle. The problem with the boxed set was that the recording engineers were sort of stunned. They'd never heard anything like that, and they didn't get a lot of it right. It got better as it went on, so Cecil Taylor's piece - the last one recorded - is technically the best recording-wise. I still think it's the best he's ever played.

Could you explain a bit about JCOA? The non-profit-making policy and so on.

It means that whatever profits there are - actually there never are any as we're always in the red - aren't supposed to benefit any one particular person. It's supposed to be channelled back into the organisation to fund further projects. JCOA puts out its own records. The main problem is distribution. We struggled along distributing ourselves, learning a lot, and by the time we got to "Escalator" we decided - since other people had started doing the same thing - there was no point in duplicating all the effort. Why not exchange information and exchange the distribution service? We started doing that in 1972 with a nucleus of ten or 12 companies - with some of the European ones like Incus, Birth, FMP, ECM. There wasn't anyone else here then except Milford Graves. We distribute 65 labels like that now, through the New Music Distributing Service - a division of JCOA, also non-profit-making.

And the reason for by-passing the establishment was that no-one wanted to take a chance on recording the new music?

Not record or distribute or promote it. And still doesn't. But it doesn't matter any more because we do perfectly well handling it ourselves. We deal with a network of about 600 stores all over the country and sell anywhere from 4,000 records a month.

Do you think the gulf between the avant-garde and the general public is growing?

No, I think the audience is getting larger all the time. You can tell that from the way popular music is going. It's constantly taking ideas from the year-ago so-called avant-garde music. The public's snapping it right up - John McLaughlin, all those people.

Why did you chose Samuel Beckett's work for your latest piece?

I guess he just expresses most aptly what I feel goes on. I don't think I take him as an inspiration for my music - music is whatever it happens to be - it's totally abstract. I wanted to find a place for his words.

What about musical inspirations?

I guess Cecil Taylor would have to be mentioned. I'm sure playing with him has an influence on what's coming out. Carla has probably influenced me, like not to go on in one direction but to let it go more melodically. I was maybe tending to get away from melody and get involved with contemporary classical music. But - all of the music that exists, you know, good and bad, is an influence. Really I haven't been listening to very much music in the last few years. Like, ten years ago, I was listening to jazz, into jazz, but I hardly listen to jazz now at all. I listen to some rock 'n' roll and enjoy it - I have the last couple of Stevie Wonder records which are nice, and I bought the new Joe Cocker record. Now John McLaughlin's band - that's something else!

And music of other cultures?

The East has probably been an influence - repetition for instance, you know, it's influenced a whole school of contemporary composers, Terry Riley, that type. That's the music I've been listening to a lot. I listen to the music of my friends. I don't like to go out and buy something to analyse.